Spahi

Spahis (French pronunciation: [spa.i]) were light-cavalry regiments of the French army recruited primarily from the Arab and Berber populations of Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco. The modern French Army retains one regiment of Spahis as an armoured unit, with personnel now recruited in mainland France. Senegal also maintains a mounted unit with spahi origins as a presidential escort: the Red Guard.

Etymology

[edit]The name is the French form of the Ottoman Turkish word sipahi, a word derived from New Persian sepâh, سپاه meaning "army", or "horsemen"; or from sipari, meaning "warriors".[1]

Early history

[edit]Following the French occupation of Algiers in 1830, detachments of locally recruited irregular horsemen were attached to the regiments of light cavalry assigned to North African service. These auxiliaries were designated as chasseurs spahis. Between 1834 and 1836 they were organised into four squadrons of regular spahis.[2] In 1841 the 14 squadrons by then in existence were brought together in a single corps of spahis. Finally, in 1845 three separate Spahi regiments were created: the 1st of Algiers; the 2nd of Oran and the 3rd of Constantine.[3]

The spahi regiments saw extensive service in the French conquest of Algeria, in the Franco-Prussian War, in Tonkin towards the end of the Sino-French War (1885), in the occupation of Morocco and Syria, and in both World Wars. A detachment of Spahis served as the personal escort of Marshal Jacques Leroy de Saint Arnaud in the Crimean War and were photographed there by Roger Fenton. A contingent of Spahis also participated in the North China campaign of 1860. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 one detached squadrons of Spahis formed part of the forces defending Paris, while a provisional regiment comprising three squadrons was attached to the Army of the Loire.[4] A serious uprising against French rule in Algeria during 1871–72 was sparked off by a mutiny of the 5th squadron of the 3rd Spahis, who had been ordered to France to reinforce those units already there.[5]

Under the Third Republic, between 1871 and 1914 Spahi units saw active service in Indochina, Tunisia, Morocco, Senegal and Madagascar.[6]

While a visually conspicuous presence in any French military force, the Spahis usually served in small detachments as scouts, skirmishers and escorts. An exception was the Battle of Isly (Morocco) in 1844 when the 1st and 2nd Spahis fought successfully as full regiments.[7]

Recruitment basis

[edit]Prior to 1914 there were four regiments of Spahis in the French Army, three based in Algeria and one in Tunisia. During their period as mounted cavalry the Spahis comprised for the most part Arab and Berber troopers commanded by French officers. This division was not absolute however and there were always a certain number of French volunteers in the ranks (for example, the later well known lyricist Raymond Asso was a Spahi between 1916 and 1919). About 20% of the rank and file were French and the remainder Arab or Berber. In addition, a fixed number of commissioned positions up to the level of captain were reserved for Muslim officers. NCOs were both French and Muslim.

In contrast to the North African tirailleur (infantry) units the mounted spahis were drawn from "the big tents": i.e. the higher social classes of the Arab and Berber communities. This dated back to the establishment of the corps when Colonel Marey-Monge[8] required that each recruit provide his own horse.[9]

As Spahi units were mechanized during World War II, the proportion of Frenchmen in the ranks increased.

World War I

[edit]Spahis were sent to France at the outbreak of war in August 1914. They saw service during the opening period of mobile warfare but inevitably their role diminished with the advent of trench warfare. During World War I the number of units increased with the creation of Moroccan Spahi regiments and the expansion of the Algerian arm. By 1918 there were seven Spahi regiments then in existence, all having seen service on the Western Front. In addition a detached squadron accompanied two squadrons of Chasseurs d'Afrique and served as part of the 5th Light Horse Brigade during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign against the Ottoman Empire. This composite force of French cavalry was known as the 1er Régiment Mixte de Marche de Cavalerie de Levant.[10] In 1918 a "marching regiment" of Moroccan spahis (Régiment de Marche des Spahis Marocains) saw active service in the Balkans, winning the collective distinction of the Médaille militaire.[11]

Between the World Wars

[edit]By 1921 the Spahi regiments had been increased to twelve (from four in 1914) and this became the permanent establishment. During the 1920s mounted Spahi regiments saw extensive active service in the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, as well as in Morocco. They continued to perform policing and garrison duties in Algeria and Tunisia, as well as providing detachments based in Metropolitan France. Although mechanisation began in the 1930s of the Chasseurs d'Afrique and Foreign Legion cavalry, the Spahis remained an entirely mounted force until after 1942.

World War II

[edit]

In 1939 the Spahis comprised three independent brigades, each of two regiments and still horse mounted. Each regiment was made up of four sabre squadrons with five officers and 172 troopers in each. Three regiments saw active service in France in 1940. Hermann Balck was of the opinion that they were the best troops that he met in both world wars.[12] One Spahi regiment (1er Régiment de Marche de Spahis Marocains) distinguished itself in service with the Free French during World War II. Garrisoned in Vichy-controlled Syria as part of a mounted cavalry unit some of the regiment crossed the frontier into the Transjordan in June 1940. After mounted service in Eritrea, this detachment was subsequently reorganised and equipped with armoured cars by the British in Egypt. The expanded and mechanised regiment served in Egypt, Libya and Tunisia, and was part of the French forces that liberated Paris in August 1944.

Post war

[edit]In the course of World War II most Spahi regiments were mechanised, but several squadrons remained mounted for patrol work in North Africa[13] plus escort and other ceremonial duties in France itself. Until 1961 the annual Bastille Day parade in Paris always featured Spahi cavalry in their traditional dress uniforms, on white Arabian horses. While Arab and Berber troopers continued to make up the bulk of numbers in the mounted units retained, mechanisation led to French personnel becoming a majority in the armoured regiments.[14]

Armoured Spahi units saw service in both the Indochina War of 1947-54[15] and the Algerian War of 1954-62.[16] The 9th Algerian Spahis remained a mounted regiment throughout the Algerian War, suffering 24 deaths in the course of active service. Except for one mounted platoon per squadron and the regimental fanfare (trumpeters) the unit was finally mechanized in 1961 and its several hundred horses either sold in Algeria or shipped back to France.

The 6th Spahis had been disbanded in 1956, followed by the 9th in 1961. Following the end of the Algerian War in 1962, the 2nd, 3rd 4th and 8th Spahis were also disbanded leaving only one, formerly Moroccan, regiment in existence as the 1st Spahis.[17]

Today

[edit]Today, the French Army retains one Spahi regiment, the 1er Régiment de Spahis Marocains;[18] an armoured unit which saw service in the Gulf War. The regiment also maintains the traditions of the entire Spahi corps as it previously existed.

Until 1984, the Regiment was located in Speyer, West Germany. Their former base there is now the Technikmuseum Speyer. The 1er Spahis are currently based in Valence, the French department of Drôme, 100 km (62 mi) south of Lyon, in the Rhone Valley, or what is commonly referred to in France as The Doors of Provence.

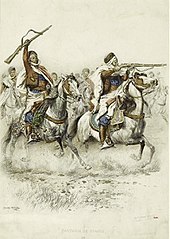

Uniforms

[edit]Throughout most of their history the Algerian and Tunisian Spahis wore a very striking Zouave style uniform. It comprised a high Arab headdress, a short red jacket embroidered in black, sky blue waist coat (sedria) a wide red sash and voluminous light blue trousers (white in hot weather).[19] The four regiments were distinguished by the differing colours of their tombeaus (circular false pockets on the front of the jacket). A white burnous was worn together with a red cloak[20] (dark blue cloak for the Moroccan Spahis after 1917).[21] French officers wore light blue kepis, red tunics with gold rank braiding and light blue breeches with double red stripes. Muslim officers wore a more elaborate version of the tenue orientale of the Arab and Berber troopers. French Spahis were distinguished by wearing a fez instead of a white Arab turban with its brown camel-hair cord. A less obvious distinction was the footwear—short sabattes or traditional North African boots in red Morocco leather for Arab/Berber troopers, conventional black leather for French troopers.[22]

From 1915, in common with other units of the Armée d'Afrique, a more practical khaki uniform was adopted for service,[11][23] but the classic red and blue tenue orientale with white burnous reappeared for parade and off-duty wear in 1927. The mounted squadrons retained for ceremonial duties wore a slightly modified version of this parade uniform, with a plain white turban, until they were disbanded in 1962. The modern 1er Spahis still wear the traditional white burnous and red sash, together with the blue cloaks of the former Moroccan regiments, for full dress. The long-skirted sand-khaki gandourah coat adopted in 1915, appears on occasion as part of the modern ceremonial uniform. Headdress is either a scarlet forage cap or the standard light blue and red kepi of the French cavalry.[24][25]

Exceptionally for a French armoured cavalry regiment, it uses gold (and not the usual silver) insignia. The "Ordonnance du Roi portant organisation de la cavalerie indigène en Algerie" of 7 December 1841 establishing the Spahis as a regular corps of the French Army specifies this distinction for sous-officers, brigadiers and officers both French and indigenous.[26]

Equipment

[edit]In 1914 spahi armament was the M1822/82 sabre of the French light cavalry together with the 1892 carbine. All harness was of dark-red red leather, of indigenous North African pattern and manufacture.[27]

Indochinese Spahis

[edit]Short-lived cavalry units designated as "spahis" were raised by the French Colonial Army in Indochina. The first of these was a squadron of spahis recruited from Cochinchina in 1861 and disbanded in 1871. The second was a small detachment of "Spahis Tonkinese" raised in Tonkin in 1883 and disestablished in 1889 for budgetary reasons.[28]

Spahis in other armies

[edit]Senegalese Spahis

[edit]

Senegal maintains a mounted cavalry detachment of spahi origin as its modern presidential security unit and ceremonial guard.

In addition to the North African cavalry, two squadrons of spahis were raised in French West Africa. The first spahis in Senegal were an Algerian detachment sent to West Africa in 1843 to deal with an outbreak of tribal conflict. This platoon-sized unit of 25 French and Algerian spahis [29] stayed and began recruiting locally. The new indigenous troopers came from the inhabitants of Senegal and the French Sudan while their French officers were seconded from Algerian Spahi regiments. The Senegalese Spahis saw extensive active service in the French West African territories of Tchad, the Sudan and the Congo between 1853 and 1898, as well as serving in Morocco between 1908 and 1919.[30]

The Senegalese Spahis were disbanded in 1928 as an economy measure[31] but provided the cadre around which a newly-raised mounted gendarmerie was formed. The modern Gendarmerie Nationale of the Republic of Senegal therefore traces its origins to the spahis, and the Red Guard still wears the burnous, fez and red tunic of the French period.

Algerian Republican Guard and Tunisian President's Bodyguard

[edit]The modern Republican Guard of Algeria includes a mounted detachment for ceremonial purposes. This unit is mounted on the same breed of white barbs as those utilised by the French spahis prior to 1962 and wear red and green uniforms with white burnouses, which broadly resemble those of their predecessors.

A similar ceremonial mounted unit is maintained as part of the Tunisian President's Bodyguard. Descended from the 4th Tunisian Spahis Regiment the modern unit retains the uniform of the French period but in the red and white of the Tunisian national colours.[32] `

Italian Spahis

[edit]The Italian colonial administration of Libya raised squadrons of locally-recruited Spahi cavalry between 1912 and 1942. The Italian Spahis differed from their French namesakes in that their prime role was that of mounted police, tasked with patrolling rural and desert areas. Although they had Italian officers, they were more loosely organised than the regular Libyan cavalry regiments (Savari). They wore a picturesque dress modelled on that of the desert tribesmen from whom they were recruited.[33]

References

[edit]- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 527.

- ^ Schollander, Wendell (9 July 2018). Glory of the Empires 1880-1914. History Press Limited. p. 440. ISBN 978-0-7524-8634-5.

- ^ Lilane and Fred Funcken, page 88, "L'Uniforme et les Armes des Soldats du XIX Siecle" volume 1, ISBN 2-203-14324-X

- ^ Stephen Shann & Louis Delperier, page 10 "French Army 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War 2: Republican Troops", ISBN 1-85532-135-1

- ^ R. Hure, page 155, L'Armee d'Afrique 1830–1962, Charles-Lavauzelle 1977

- ^ Schollander, Wendell (9 July 2018). Glory of the Empires 1880-1914. History Press Limited. p. 441. ISBN 978-0-7524-8634-5.

- ^ Schollander, Wendell (9 July 2018). Glory of the Empires 1880-1914. History Press Limited. p. 440. ISBN 978-0-7524-8634-5.

- ^ Schollander, Wendell (9 July 2018). Glory of the Empires 1880-1914. History Press Limited. p. 440. ISBN 978-0-7524-8634-5.

- ^ Douglad Porch, pages 71-72 "The Conquest of Morocco", ISBN 0-333-44461-2

- ^ "1er Régiment Mixte de Cavalerie Du Levant". Australian Light Horse Studies Centre. 28 June 2009. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ a b Jouineau 2009, p. 59.

- ^ https://de.scribd.com/doc/153227108/Balck-Interview Balck's interview with US Army, page 7.

- ^ Glogowski, Ohilippe (2012). Histoire des Spahis Tome 2 - de 1919 a'nos jours. pp. 26–29. ISBN 9-782843-786211.

- ^ Jouineau, Andre (2012). Officers and Soldiers of the French Army of the Victory. Histoire & Collections. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9-782352-5026-16.

- ^ Windrow, Martin (15 November 1998). The French Indochina War 1946-54. Bloomsbury USA. p. 16. ISBN 1-85532-789-9.

- ^ Morgan, Ted (31 January 2006). My Battle of Algiers. HarperCollins. pp. 72 and 76. ISBN 0-06-085224-0.

- ^ Robert Huré, L'Armee d'Afrique, Charles-Lavauzelle (1977) OCLC 3845831, p. 462

- ^ Montagnon, Pierre (2012). L'Armee d' Afrique. Pygmalion. p. 431. ISBN 978-2-7564-0574-2.

- ^ Montagon, Pierre. L'Armee d'Afrique. De 1830 a l'independence de l'Algerie. p. 94. ISBN 978-2-7564-0574-2.

- ^ Schollander, Wendell (9 July 2018). Glory of the Empires 1880-1914. History Press Limited. pp. 441–445. ISBN 978-0-7524-8634-5.

- ^ Mirouze, Laurent (2007). The French Army in the First World War - to Battle 1914. Uniforms - Equipment - Armament (Volume 1). Militaria. ISBN 978-3-902526-09-0.

- ^ Mirouze, Laurent (2007). The French Army in the First World War (Volume 1). Militaria. pp. 390–391. ISBN 978-3-902526-09-0.

- ^ "Notice descriptive des nouveaux uniformes. (Décision ministérielle du 9 décembre 1914 mise à jour avec le modificatif du 28 janvier 1915)" (in French). Paris: Ministère de la Guerre. 1915. Retrieved 2021-07-30 – via Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

- ^ Galliac, Paul (2012). L' Armee Francaise. p. 20. ISBN 978-2-35250-195-4.

- ^ Coune, Frederic. "Kepi. Une coiffure franchise".Tome 2. p. 10. ISBN 979-10-380-1340-7.

- ^ Pierre Rosiere, p52 "Spahis - des spahis algeriens aux gardes rouges de Dakar", ISBN 2-901151-15-9

- ^ Mirouze, Laurent (2007). The French Army in the First World War (Volume 1). p. 391. ISBN 978-3-902526-09-0.

- ^ Maurice Rives, page 42, "Les Linh Tap", ISBN 2-7025-0436-1

- ^ Pierre Rosiere, "Spahis - des spahis algeriens aux gardes rouges de Dakar", ISBN 2-901151-15-9 p. 60

- ^ Pierre Rosiere, "Spahis - des spahis algeriens aux gardes rouges de Dakar", ISBN 2-901151-15-9 pp. 121-122

- ^ Pierre Rosiere, "Spahis - des spahis algeriens aux gardes rouges de Dakar", ISBN 2-901151-15-9 p. 137

- ^ Rinaldo D. D'Ami, page 46 "World Uniforms in Colour", Volume 2, Patrick Stephens Limited 1969, SBN 85059 040 X

- ^ Plates I & IV, "Under Italian Libya's Burning Sun", The National Geographic Magazine August 1925

Sources

[edit]- Jouineau, André (2009) [2009]. Officiers et soldats de l'armée française Tome 2 : 1915-1918 [Officers and Soldiers of the French Army Volume II: 1915-18]. Officers and Soldiers #12. Translated by McKay, Alan. Paris: Histoire & Collections. ISBN 978-2-35250-105-3.

- Charles Lavauzelle. "L'Armee d'Afrique 1830–1962"

- Paul Oddo. "Calots Rouges et Croix de Lorraine - Les Spahis de Leclerc"

- Pierre Rosiere. "Spahis - des spahis algeriens aux gardes rouges de Dakar"

- Ian Sumner. "The French Army 1914–18" ISBN 1-85532-516-0.

- Furlong, Charles Wellington (1914). "Turcos And The Legion: The Spahis, The Zouaves, The Tirailleurs, And The Foreign Legion". The World's Work, Second War Manual: The Conduct of the War: 35–37. Retrieved 2009-08-16.